Ceramic Installation Variables Worthy of Careful Scrutiny

This article may be brief. But that's not to insinuate that the information covered herein is not of extreme importance relative to ceramic tile installation. I urge you to thoroughly digest the topics I raise. Hopefully, you'll learn a thing or two that will help you avoid costly callbacks in the future.

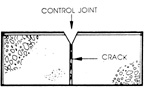

Control and expansion joints. Anti-fracture, crack-isolation and crack-suppression membranes all fall within the same family of products. The problems that occur most frequently lie in the treatment(s) employed to protect tile and dimensional stone over control joints.

Control joints should be used as a guide for placing the tile or stone in a crack-free position. In addition, a soft joint should be installed -- even when using a membrane. Some membrane manufacturers have systems that they say will work over control joints. However, the Tile Council of America (TCA) does not recommend a method for tiling over joints with a membrane.

When joints are involved, avoid the use of scribing paper, building paper and roofing felt. These products are susceptible to moisture and de-bonding. In addition, the resulting bond will be weak and, to the latest litigators' delight, mold growth may occur. Use of these materials may be the cheapest way to go, but it's the most hazard-prone path to follow.

Tilework over expansion joints must always contain soft joints, because you can almost always be certain to experience movement due to moisture, sunlight, temperature and structural settling.

The allowable warpage of large-sized tile further compounds the problem. Because of these problems, manufacturers have developed specialty materials -- such as medium-bed mortars -- that help mitigate slab deficiencies and excessive tile warpage. It may be possible to do an acceptable installation if you work with these products as directed by the manufacturer.

Proper transfer. Acceptable transfer may not be accomplished by the normal beating-in practice. A new trowelling method developed by the National Tile Contractors Association (NTCA), where straight trowel beads are utilized, will improve your transfer.

Moisture-related problems. A plethora of troubles can emerge in installations subject to moisture exposure. Among these are:

It is wise to conduct a moisture test using, at the very least, an electronic meter for fast and accurate interpretation before the installation begins.

Presence of old cut-back adhesive. Old cut-back is very difficult to remove. The surest way to be rid of it is through shot-blasting. However, certain mortar manufacturers produce a mortar that can safely be used over old cut-back, provided the remaining adhesive is scraped thoroughly. This is an important consideration because moisture and alkali, presuming it appears sometime after the installation is complete, can soften the old cut-back and result in tile de-bonding.

Avoid the use of chemicals to remove old-cut back if you are planning to use a mastic. The residue of the cleaning agent in the concrete pores may attack your mastic and render it ineffective.

Carpet adhesive residue. These adhesives are significantly affected by moisture and alkali to the point of preventing a good bond. As with old cut-back, thoroughly remove the carpet adhesive prior to the tile installation.

A simple solution to old latex adhesive problems is the application of a Portland cement-based skim coat specifically designed for this purpose.

- Wall tile grout not packed solidly.

- Use of excessive mixing water (water evaporates and the grout shrinks).

- Excessive deflection.

- Remixing of grout with water after hydration has already started.

- Movement of the substrate.

- Use of unsanded grout in large grout joints.

Discoloration is also high on the list of grout-related defects. Causes include:

- Too much mix water in grout.

- Use of unclean water.

- Wiping the grout too soon and with too much water.

- Having too much mortar in grout joint (two-thirds of the joint depth needs to be left open).

- Poor curing.

- Tiles with overglaze causing uneven hydration and uneven curing of grout. (Reject overglazed tiles.)

- Not allowing the grout to slake (slow down).

- Use of old grout mix.

In large wall areas, particularly within commercial environs, it is wise to never leave a wall partially grouted -- even when you plan to finish grouting the next day. I've seen instances in which the same crews returned to finish the job the next morning but the previously installed grout wound up with a different shading than the subsequently installed grout. This comes about due to variation in the job site conditions, i.e. a sunny day vs. a rainy day. In such cases, the grout cured at different rates from one day to the next. This, in turn, affected the coloring.

Caulk vs. grout. Many of the ceramic tile inspections I have conducted -- when they didn't involve cracked tile, lippage, etc. -- were precipitated by the improper use of Portland cement grout in areas where caulk should have been used.

This improper use resulted in grout cracking, pulling away from the wall and exposing an opening that would allow water to enter and, perhaps in the future, create a mold problem. This is especially prevalent in new home construction on countertops and in the shower areas where the floors abut the walls.

There are various reasons why Portland cement grout is used when a caulk should be. Among them are:

- The caulk may not match the grout color.

- The better-quality caulks are more difficult to apply.

- Economic reasons -- caulk is relatively expensive and will also slow installation productivity.

This may seem like a lot of variables to be mindful of. The good news is most of the resulting problems can be avoided simply by exercising a little bit more caution and care.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!