Focus on Resilient: If you are installing on concrete, get the hard facts

Among the many questions we get from NFT

readers, there always seems to be a few regarding commercial flooring and the

concrete that lies beneath. Specifically, installers and others in the trade

wonder about the downside risk of installing resilient flooring on a substrate

that has not been adequately prepared. They wonder about the effect on the

resilient flooring products and adhesives. They ask what to look for and how to

avoid costly claims. They say it is a persistent issue-particularly as more

dealers look to the commercial market to offset sluggishness on the residential

side. With this in mind I put together some of the more frequent concerns and

how to cope with them. I would like to share this with our readers.

Among the many questions we get from NFT readers, there always seems to be a few regarding commercial flooring and the concrete that lies beneath. Specifically, installers and others in the trade wonder about the downside risk of installing resilient flooring on a substrate that has not been adequately prepared. They wonder about the effect on the resilient flooring products and adhesives. They ask what to look for and how to avoid costly claims. They say it is a persistent issue-particularly as more dealers look to the commercial market to offset sluggishness on the residential side. With this in mind I put together some of the more frequent concerns and how to cope with them. I would like to share this with our readers. The No. 1 question, of course, is: What shape should the concrete be in to receive resilient flooring material? From there other questions arise. The situation is not helped by confusion over the expression “minimal concrete floor preparation.” This is a description that is frequently misconstrued and misapplied. There is plenty of misinformation about the installation process, so let’s start with a few simple “yes” or “no” questions to test your general knowledge of concrete sub-floors:

• Is concrete smooth enough to install resilient flooring material without additional prep?

• Is it the responsibility of the flooring installer to correct the work of a concrete contractor?

• Should the installer be responsible for crack repair, trowel chatter or soft surfaces caused from excess bleeding of the concrete? • Is it the installer’s job to grind down the high spots that come from slab curl or improper concrete finishing? • Should the installer be responsible for skim coating a rained out slab or surface spalling of a slab? • Is the installer the one who must skim coat an entire slab because it is poorly finished? The answer to every one of these questions is “NO!” The flooring installation team (or flooring contractor) should be counted on to patch an occasional hole and/or surface damage from the construction work, but not much else. The concrete should be in good repair and ready to be broom swept, but that’s it. Too often the installers are coerced into doing additional floor prep by the general contractor. Why? Because we let them get away with it.

There are ongoing discussions between the concrete industry and the flooring industry about how the concrete surface should be finished. Some say the concrete should be burnished to a high sheen. That may look pretty but it’s not functional. Flooring installers need a surface profile that enhances the bond between adhesive and substrate. This is especially true when an epoxy is used. Adhesives must be able to achieve a mechanical bond and that is difficult if the concrete is left with a hard trowel finish. To help address this, the American Concrete institute (ACI) has devised a means to determine floor flatness (FF) and floor levelness (FL) on a concrete slab. The FF and FL factors are designed to replace the 1/4” in 10’ we are most accustomed to and are on a logarithmic scale. These numbers are calculated so that the higher the number, the flatter and more level the concrete floor. The ACI current specification for a slab on grade is FF 35 / FL 25. (To help understand this, a FF 20 is twice as flat as a FF10 and only half as flat as a FF40.) Unfortunately, the average slab in North America is FF 18. There is no correlation between the floor flatness factors and the straightedge tests in 6’ or 10’. Remember, the concrete industry has super flat slabs at FF 300, so it can be done. Still, the problem with concrete slabs is that floor flatness tests are normally performed about two weeks after the concrete hardens. As the concrete continues to dry the floor flatness factors change.

Then of course we have issues related to the presence of coal, lignite, shale and clay. These foreign materials-collectively known as “expansive aggregate”-are an issue in several areas of North America where they get into the concrete mix. When this happens the materials expand with surface moisture and create a lumpy effect to the concrete surface. This generally occurs after the floor covering has been installed and it shows through the finished floor. Sealers and curing compounds Installers wonder why flooring manufacturers specify not to use any type of curing, sealing or parting compound on the surface. (This advice is also found in ASTM F-710 “Specifying Concrete Slabs to Receive Resilient Floor Coverings.”) The reason is caution. Flooring manufacturers do not (and cannot) keep up with all the curing, parting and sealing compounds that are used on the surface of the concrete. These materials can impact the way an adhesive bonds to the concrete. In some cases they are incompatible with adhesives.

Curing compounds are applied to the slab to hold the moisture in the slab. They are designed to degradate over time. Unfortunately, some are put on heavy and some lightly. This means the moisture will sometimes release quickly and sometimes more gradually.

Sealers, meanwhile, are applied to create a walking surface. The idea is to control dusting, not to serve as a substrate. Parting compounds (also known as “bond breakers”) are designed to facilitate “tilt-up construction”-walls are poured on the slab, then tilted up into place. If any of these compounds are used, they must be removed prior to the flooring installation. Failure to do so can result in an adhesive failure. So if concrete has so many moisture problems why don’t they make a fast-drying concrete? Let’s just say it’s on the horizon. Engineers are testing a self-desiccating concrete. It is supposed to dry to 3 lbs. per 1,000 sq. ft. per 24 hours, on the calcium chloride test in 80 days. Time will tell if this will help solve some of the moisture problems. The bad news is it is going to be at a much higher cost than regular concrete.

Moisture testing concrete One question I often hear from installers is what is the best method for moisture testing concrete, the calcium chloride or the hygrometer probe test? That depends on what and how you are testing. If you go with the calcium chloride test remember there are many factors that can affect the outcome: temperature, humidity, the slab equilibrium, how well the slab was cleaned and the duration of the test. The calcium chloride test measures moisture vapor emissions rate (MVER) and will only measure the top 1/2” to 3/4” of the slab. You can expect “false positives” if the slab is not in equilibrium, the humidity is too low or the slab is not cleaned down to bare concrete. This can also happen if the test time is too short. If the temperature is too high you will get false negatives. The hygrometer probe gives you more accuracy and less worry about job site conditions. The probe measures the internal relative humidity at a depth equaling 40 percent the thickness of the slab. The depth should go no further than 40 percent ( about 1” -3/4” on a 4” slab) because it marks the apex of the drying curve. Once the slab reaches equilibrium, that is where the test result will be.

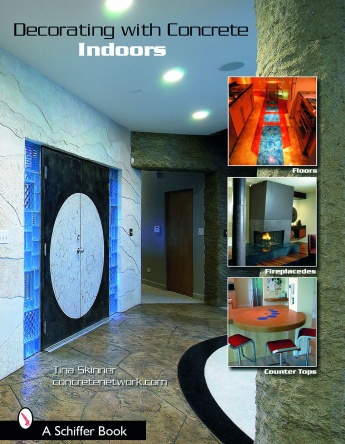

A

big concern for installers working with resilient flooring should be the

condition of the concrete that lies beneath. They should be willing to patch

some surface damage from the construction work, (as seen here) but not much

else. Remember, it is not the installer’s responsibility to correct the work of

a concrete contractor.

Among the many questions we get from NFT readers, there always seems to be a few regarding commercial flooring and the concrete that lies beneath. Specifically, installers and others in the trade wonder about the downside risk of installing resilient flooring on a substrate that has not been adequately prepared. They wonder about the effect on the resilient flooring products and adhesives. They ask what to look for and how to avoid costly claims. They say it is a persistent issue-particularly as more dealers look to the commercial market to offset sluggishness on the residential side. With this in mind I put together some of the more frequent concerns and how to cope with them. I would like to share this with our readers. The No. 1 question, of course, is: What shape should the concrete be in to receive resilient flooring material? From there other questions arise. The situation is not helped by confusion over the expression “minimal concrete floor preparation.” This is a description that is frequently misconstrued and misapplied. There is plenty of misinformation about the installation process, so let’s start with a few simple “yes” or “no” questions to test your general knowledge of concrete sub-floors:

• Is concrete smooth enough to install resilient flooring material without additional prep?

• Is it the responsibility of the flooring installer to correct the work of a concrete contractor?

• Should the installer be responsible for crack repair, trowel chatter or soft surfaces caused from excess bleeding of the concrete? • Is it the installer’s job to grind down the high spots that come from slab curl or improper concrete finishing? • Should the installer be responsible for skim coating a rained out slab or surface spalling of a slab? • Is the installer the one who must skim coat an entire slab because it is poorly finished? The answer to every one of these questions is “NO!” The flooring installation team (or flooring contractor) should be counted on to patch an occasional hole and/or surface damage from the construction work, but not much else. The concrete should be in good repair and ready to be broom swept, but that’s it. Too often the installers are coerced into doing additional floor prep by the general contractor. Why? Because we let them get away with it.

There are ongoing discussions between the concrete industry and the flooring industry about how the concrete surface should be finished. Some say the concrete should be burnished to a high sheen. That may look pretty but it’s not functional. Flooring installers need a surface profile that enhances the bond between adhesive and substrate. This is especially true when an epoxy is used. Adhesives must be able to achieve a mechanical bond and that is difficult if the concrete is left with a hard trowel finish. To help address this, the American Concrete institute (ACI) has devised a means to determine floor flatness (FF) and floor levelness (FL) on a concrete slab. The FF and FL factors are designed to replace the 1/4” in 10’ we are most accustomed to and are on a logarithmic scale. These numbers are calculated so that the higher the number, the flatter and more level the concrete floor. The ACI current specification for a slab on grade is FF 35 / FL 25. (To help understand this, a FF 20 is twice as flat as a FF10 and only half as flat as a FF40.) Unfortunately, the average slab in North America is FF 18. There is no correlation between the floor flatness factors and the straightedge tests in 6’ or 10’. Remember, the concrete industry has super flat slabs at FF 300, so it can be done. Still, the problem with concrete slabs is that floor flatness tests are normally performed about two weeks after the concrete hardens. As the concrete continues to dry the floor flatness factors change.

Then of course we have issues related to the presence of coal, lignite, shale and clay. These foreign materials-collectively known as “expansive aggregate”-are an issue in several areas of North America where they get into the concrete mix. When this happens the materials expand with surface moisture and create a lumpy effect to the concrete surface. This generally occurs after the floor covering has been installed and it shows through the finished floor. Sealers and curing compounds Installers wonder why flooring manufacturers specify not to use any type of curing, sealing or parting compound on the surface. (This advice is also found in ASTM F-710 “Specifying Concrete Slabs to Receive Resilient Floor Coverings.”) The reason is caution. Flooring manufacturers do not (and cannot) keep up with all the curing, parting and sealing compounds that are used on the surface of the concrete. These materials can impact the way an adhesive bonds to the concrete. In some cases they are incompatible with adhesives.

Curing compounds are applied to the slab to hold the moisture in the slab. They are designed to degradate over time. Unfortunately, some are put on heavy and some lightly. This means the moisture will sometimes release quickly and sometimes more gradually.

Sealers, meanwhile, are applied to create a walking surface. The idea is to control dusting, not to serve as a substrate. Parting compounds (also known as “bond breakers”) are designed to facilitate “tilt-up construction”-walls are poured on the slab, then tilted up into place. If any of these compounds are used, they must be removed prior to the flooring installation. Failure to do so can result in an adhesive failure. So if concrete has so many moisture problems why don’t they make a fast-drying concrete? Let’s just say it’s on the horizon. Engineers are testing a self-desiccating concrete. It is supposed to dry to 3 lbs. per 1,000 sq. ft. per 24 hours, on the calcium chloride test in 80 days. Time will tell if this will help solve some of the moisture problems. The bad news is it is going to be at a much higher cost than regular concrete.

Moisture testing concrete One question I often hear from installers is what is the best method for moisture testing concrete, the calcium chloride or the hygrometer probe test? That depends on what and how you are testing. If you go with the calcium chloride test remember there are many factors that can affect the outcome: temperature, humidity, the slab equilibrium, how well the slab was cleaned and the duration of the test. The calcium chloride test measures moisture vapor emissions rate (MVER) and will only measure the top 1/2” to 3/4” of the slab. You can expect “false positives” if the slab is not in equilibrium, the humidity is too low or the slab is not cleaned down to bare concrete. This can also happen if the test time is too short. If the temperature is too high you will get false negatives. The hygrometer probe gives you more accuracy and less worry about job site conditions. The probe measures the internal relative humidity at a depth equaling 40 percent the thickness of the slab. The depth should go no further than 40 percent ( about 1” -3/4” on a 4” slab) because it marks the apex of the drying curve. Once the slab reaches equilibrium, that is where the test result will be.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!